Ability

4 min read

I came across this blog post from the Chalkboard project, and it's an interesting read less for what it says, and more for what it omits.

For example:

For the last decade, in particular, on a nationwide basis we have spent billions of dollars trying to improve reading achievement. We have spent lavishly on special education, the latest curriculum programs, response to intervention strategies, early childhood literacy programs, staff development programs, technology-based remedial programs – and yet achievement has not improved. Again, how can this be?

Some other things that have happened in the last decade:

- Food insecurity increased, both in Oregon and across the United States;

- While much money was spent, much of it was spent on requirements set down within NCLB. Schools, teachers, and students can't be blamed for mandates handed down from uninformed politicians.

- Expensive programs of dubious value (I'm looking at you, Reading First) soaked up even more cash.

- The constraints of No Child Left Behind and shrinking budgets contributed to shorter class time, and fewer enrichment classes. It's interesting to read the first article (from 2006) and compare it to the more recent, 2011 piece.

- And then there's that whole economy collapsing thing.

I could go on, but hopefully you get my point. A lot has happened in the last ten years; if we want to have a chance at improving our schools, we can't pretend that context doesn't matter.

But back to the Chalkboard piece.

The author states:

The primary effects of ability differences are seen in variations in the rate, quality and retention of learning experienced by different students. Lower ability students need more explicit instruction and practice to mastery concepts and skills, are more prone to misconceptions needing detection and correction, and don’t retain as much in memory needing more structured review over time. The consequence is that successful, long term learning for lower ability students requires more time.

In this section - really, the meat of the piece - the author lays out his thesis. This thesis is crippled at the outset, as his definition of "ability differences" seems to imply that ability can be defined by a single facet. In fairness, he is discussing reading scores, so an argument can be made that "ability" in this context is limited to "reading ability."

But, even that crutch gets tossed out the window when we get into the discussion about "lower ability students." The author states that the only way for these "lower ability students" to achieve the same as their higher ability (read "smart") peers is for an increased use of "explicit instruction" and "correction." This sounds a lot like telling the dumb kids they need to sit down, shut up, and listen. No creative problem solving for you.

The piece ends with three questions, and with some editing they could be the start of something worthwhile:

(1) What is the psychological rationale for the current standards-based assessment system?

(2) Why aren’t the measurement and reporting of individual student growth the center point of the current state assessments?

(3) Why is cognitive ability not systematically measured and used to predict achievement?

Question 1 could be edited to: What is the rationale for tethering our measure of student growth and learning to a set of external standards that does not necessarily reflect that student's academic needs?

Question 2 could be edited to: Why aren't the strengths, achievements, and growth of each student reflected in how students are assessed at the state level?

Unfortunately, there really isn't any saving question 3, as any measurement is only as good as the time when it was taken. If a student's "cognitive ability" was assessed on a day when they had missed dinner the night before, breakfast that morning, and their mother had been out of work for the last three months, yeah, they'll have other things on their mind besides a stupid test.

Students don't exist to provide us data points. They are people, and as we get into the meat of determining "ability" we would do well to remember that ability can mature or fade over time. As we parse through the various conversations and suggestions that people are offering about education, we need to make the time to take a step back, look at the larger context, and realize that learning and excellence are things we pursue over a lifetime. None of us are complete at the end of the fourth grade, or the eighth grade, or high school. We can assess what happens there, and look to improve the process, but the important things we learn are inherently personal, and don't fit well within a scantron.

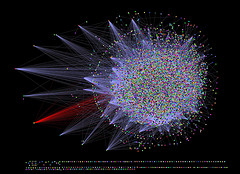

Image Credit: "HumanInteractome3" taken by andytrop79, published under an Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives license.