Step Away From The Big Data

5 min read

I ran across this article summarizing an event put on by the New York Times called Schools For Tomorrow. The article focused in on the use of data in education, and it exhibits some of the trademarks of bad education reporting.

The article states by attempting to define what is being billed as the problem:

Right now, schools teach and test every student the same way, even though children have different ways of learning not used in the classroom. But educators are starting to use data analytics to make in-depth assessments of each student and how he or she learns.

No matter how many times this gets repeated, it's not true - although, the rollout of high stakes tests used in teacher and school evaluation as part of the Common Core implementation pushes us in this direction. This definition of the problem makes the most sense to people who are marketing "solutions" that personalize learning - and this definition ignores some basic realities about teaching and learning.

Educators have been using direct observation of students - combined with training and experience - to personalize learning for decades. Smaller classes make this easier to do. The lie of the "one size fits all" myth is that data, and only data, can lead to an effective analysis of learner's needs.

The piece goes on to quote Alec Ross:

Alec Ross, a senior advisor on innovation at the U.S. State Department and former senior advisor to Secretary Hillary Clinton, feared the Achievement Gap would actually widen because analytics would favor those who could afford the examination.

He compared it to what's called a "CEO Checkup," where he claims CEOs of the largest firms will spend $75,000 for a seven to eight-hour thorough physical examination by the best doctors in the world, something the plebeians will never get.

"A lot of what I see is the ability to productize and commercialize very intensive assessments of individual limits. So what I imagine is parents getting their kids essentially a $30,000 educational checkup where they extract enormous amounts of data about the kinds of learners their children are, the kinds of education deficits they have," he said.

The observation that companies are racing to "productize and commercialize" data analysis is spot on, but the fear that this will create haves and have-nots is late: we already have haves and have-nots, largely based on socioeconomic status. The pursuit of personalization through big data will divert a large amount of public money into private companies, but the reality is that people of means have access to a great education - with adequate attention to the needs of the individual learner - and those with less means have fewer options.

Of course, no piece of bad education journalism is complete without the "D" word:

Michael Horn, co-founder of The Clayton Christensen Institute for Disruptive Innovation said some public schools are taking the data to drive better learning experiences in an optimized model.

A lot (arguably, far too much) has been written about "disruption" and education. It's worth noting that the point of disruption is not to create something better or innovative. The goal of what gets called a disruptive innovation is to create something whose low cost justifies its relative mediocrity. So, while the techno-utopian wing of the education reform discussion likes to trumpet big data as the gateway to personalization, the reality looks a lot like Rocketship Academy, with 70+ students in a room sitting in front of computers with a single underpaid aid. The nature of a disruptive innovation isn't quality, but expense. A disruptive innovation succeeds not because it is better, but because it is cheaper - and this is not a good paradigm for educational improvement.

Advocates for a data driven approach seem to overlook that we already have evaluations of cognitive ability and evaluations of learning differences. These tests are administered regularly by trained professionals to help assess students with learning differences. It's unclear whether advocates for big data are unaware of these tools, or just disdainful of them because they have a paper and pencil track record, but pretending that they don't exist - and ignoring how they have helped learners - isn't honest or efficient. Currently, families with more money have greater access to diagnostic and evaluative tests because of expense, and in some cases, because of the quality of health insurance, as there are circumstances where assessments are a covered expense.

Data has its place, without doubt. Arguably, the goal of automated analysis of educational data is to replace the well trained humans currently doing comparable work. But in the examination of how data could be used to help people learn, we need to acknowledge that the problems data is attempting to solve already have solutions. While people are willing to spend millions on data collection systems that might not deliver, they are unwilling to spend thousands on additional teachers to reduce class sizes, and on additional training for teachers on how to design and read assessments. Investment in big data has the mystical appeal of a silver bullet, where investing in people just sounds like work. We need to step away from our data fetish.

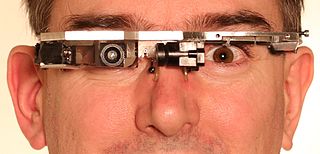

Image Credit: Eye Crop, from Wikipedia, released under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike license.