Understanding Open Content By Talking About Good Teaching

5 min read

On Saturday, March 9th, we held an Open Content authoring day in San Francisco. It's the second we've put on this year, and for those interested, we have a third coming up in Portland, OR on April 6th.

The San Francisco meetup was held on the campus of Lick Wilmerding, made possible thanks to Jonathan Mergy. In the morning of the meetup in San Francisco, we spent some time working with the participants on converting existing lessons - stored in word docs, google docs, or as collections of files - into more granular, more easily reusable, chunks of information.

The work of transitioning existing instructional material into reusable open content is largely organizational, and involves reviewing and editing existing material to ensure that it is well organized and coherent. However - and this point cannot be emphasized enough - this review and editing process results in better material. This is something that, in an ideal world, would happen anyways. This review should be viewed through the lens of supporting better instructional design, and should be incorporated as part of ongoing teacher professional development. The process of organizing a lesson to make it easier to reuse as open content is EXACTLY THE SAME as reviewing a lesson to make sure it is coherent.

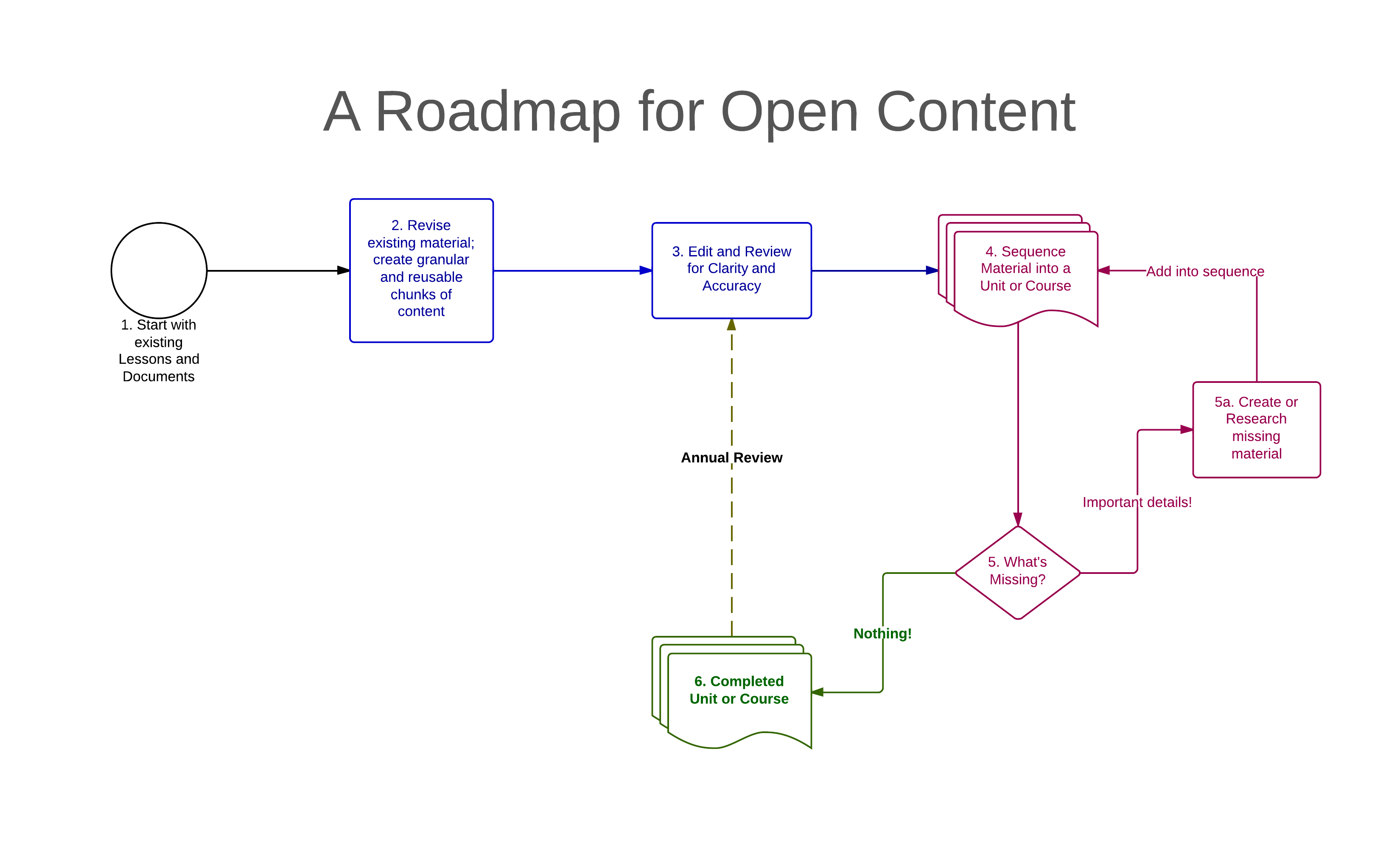

In the afternoon, the discussion included sketching out a rough road map for an entire school to transition to a broader, more regular use of open content. The key element in this transition involves reinforcing the idea that the process of creating open content is identical to the process of creating any other type of content - the only substantial difference is the license that is applied to the work. It sounds obvious, but when discussing open content, the notion of openness - and the new horizons implied by the philosophical shift in focus - often distract us from the familiar act of creating useful educational material.

The starting point for individual teachers, a department, or an entire school is exactly the same: the individual lessons that teachers have already created, currently stored on hard drives, in Google docs, in notebooks, and/or in filing cabinets. These lessons exist; many of them have been tested and revised multiple times. Cleaning up this existing source material - a practice that leads to better instructional design, and a practice that should be happening anyways - provides a starting point. It's also worth noting that teachers working in groups, revising the lessons of their colleagues, provides natural opportunities for peer mentoring.

In an earlier post, we talked about the steps involved in creating open content. Working teachers have already done the first steps. Most are at the point where they can edit and revise to make their work clearer - and, as a side benefit, easier to reuse.

Teachers have lessons and other educational materials. They create them regularly, and use them every day.

Like just about anything, this material can benefit from review, and this review can include reorganization into a structure that makes it easy to reuse the lessons.

Once the lessons have been edited and restructured, they can be sequenced into a unit or a course. At this point, the goals of the unit or course can be used to determine what additional material, if any, is needed to round out the work. If any new material is needed, it can be created, or sourced from other openly licensed content.

In practice, this would look something like this:

The review process - steps 2 and 3, where existing lessons are converted into smaller, more granular components, would occur periodically throughout the year. The process of sequencing the lessons - step 4 - would occur less regularly - perhaps 2-3 times a year - with a semi-annual review session - step 5 - dedicated to cleaning up full courses by filling in any gaps that aren't met with the material that has already been created. This way, the work unfolds gradually, and is a natural extension of the work already required to teach a course, and to prepare for upcoming classes. The process can be sped up, of course, but that requires more focused time, and people who have both the content area expertise and the available time to do the work. If this was implemented at the department level - with all teachers in a department collaborating over the course of a year on focused lesson cleanup - the first year would produce a solid body of work, and the second year could allow for greater levels of experimentation and sophistication - for example, Chemistry and Biology teachers and students could generate some 3d molecular models that could be incorporated into science texts.

But in any case, when we talk about creating open content, the discussion needs to be framed around the act of creating. Teachers are already doing this work, and many teachers are already on board with sharing their work to benefit others. However, we have found calling this process "creating open content" confuses the issue. When we are introducing people to the concept of open content, we need to talk less about the licensing issues, and more about sound instructional design. It sounds counter-intuitive, but we have found that by reinforcing what teachers know, and how that pre-existing knowledge dovetails cleanly with the new concept of open licensing, people understand the new concept - open licensing - more fully, even though we talk about it less. Open content is good teaching, and this is the discussion that we need to be having.