Reclaiming Personalized Learning

8 min read

I landed my first job teaching late in the winter, about eight months after I graduated college. I was hired by a school district near Boston to tutor a 15 year old kid - a sophomore - who had gotten expelled from school for pulling a knife on another kid. I was his tutor for his core academic subjects - English, History, Algebra, Biology. I learned later that no one expected him to show up, but as I hadn't been let in on that secret yet, I made the time to go and meet with all of his teachers, find out where he had left off in the curriculum, and hopefully (and yes, I recognize how hopelessly naive this sounds) get some insight into what he was like as a student.

Bob's teachers (that's not his name, but that's what we'll call him in this story) were not excited to talk with me. His English, History, and Algebra teachers refused to meet with me, and his Biology teacher met me with some questions of his own.

"Why are you here?" he asked me, as he gave me photocopies of a textbook, along with tests and quizzes. "In the time that we have talked today, I've seen more of you than I've seen of Bob in the last month. What do you really think you'll accomplish here?"

I mumbled something about wanting to make a difference, but really, I hadn't thought about it that much.

But the screwy thing was, Bob showed up, and kept showing up. We met at the Brookline Public Library. We spent two hours each weekday covering the four core subjects; I assigned homework, along with quizzes, tests, papers, and other assignments. And for the most part, he did the work. After I had been stood up by his English teacher, I asked my boss - who worked in the office of Home and Hospital Instruction - if I could have some latitude in book selection. She looked at me funny, and a couple days later gave me a book list. I stopped reading it as soon as I saw that A Clockwork Orange was on there, and the next day, Bob got a library card, checked out the book, and started reading.

And so things went for about a month. On Fridays, I would go down to the district office, hand in my time sheet and Bob's completed and graded work, talk with the receptionist, and then go home.

Then, on a Monday, Bob didn't show up. On Tuesday either. Over the weekend, we had started in on one of the unnaturally warm stretches that can slip into long Northeastern winters - somewhere between three to seven days of sunshine, and warmth that tempts you into thinking that winter is done. I left messages at his house - this was in the dark ages, before cell phones, before texting, before even email was in mainstream use - but had heard nothing back. I figured I had lost Bob to the weather, and maybe for good. On Wednesday, though, he was there - ten minutes late, but there.

"What's up," I asked. "Where were you?"

Bob was always pretty quiet. He was a tall kid - taller than me - and skinny, with the beginnings of a peachfuzz mustache that probably wouldn't require shaving until he was in his twenties. But today, when he spoke, he was quieter than normal, and I had to lean in to hear him. "My friend got shot."

"When?"

"I'm not completely sure," Bob said. "Either Sunday night or Monday morning."

"You okay?" I asked him.

He nodded.

"You involved?" I asked.

He shook his head, no.

"I don't know who did it though. And I don't know if he's okay."

"You want to try and find out?"

Bob looked up. "Yeah. How?"

And that day, I showed Bob how to do basic research within a newspaper - nothing big, but the library had the print versions of the Globe going back two weeks, and we started with the Metro section, and we broke down how the whole paper was organized. The reference librarian also got into the mix, and I let Bob know that reference librarians know how to find out about everything. After around forty-five minutes, Bob found a blurb that gave him information about his friend - he had been shot late Sunday night, had been taken to a hospital, and was in stable condition.

After that day, I continued tutoring Bob for the next few weeks; eventually he was placed in a halfway house for at-risk youth, and I don't know what happened with him after that. On my last week, when I handed in my time sheet, I met with my boss.

"Most of the time, these things don't last more than a week," she told me.

It took me a second to realize that "these things" meant a kid working with a tutor.

"Most kids stop coming, if they even come at all. We do what we can, but once a kid has been expelled, we don't have a lot of options. Seven weeks is probably some kind of record."

I think about Bob, and the kids like him, when I hear about people talking about how "Big Data" will save education, and enable more effective "personalized" learning.

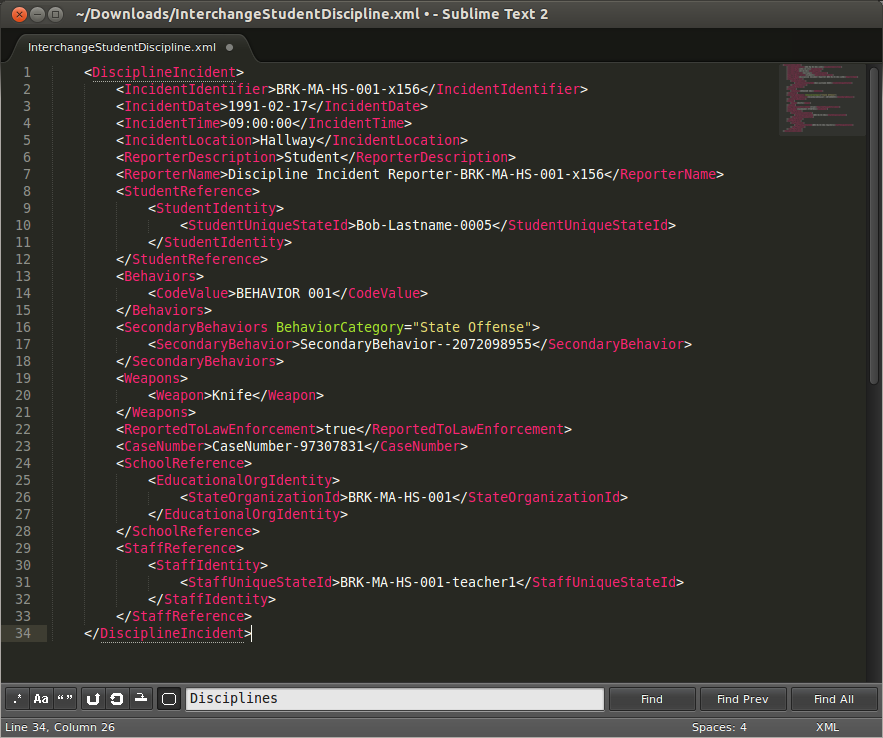

And I wonder what Bob would look like in one of these systems:

The great thing about data is that, with enough points, we begin to have a collection of information against which we can begin to look for patterns, and, hopefully, to ask good questions. But the bad thing about data is that it looks suspiciously like a fact, which leads to good data being put to bad use. Additionally, it can mislead people into thinking that activities that don't produce a data trail are somehow less worthwhile.

The push for more "personalized" learning is occurring against a backdrop where teachers - and teacher's unions - are being blamed for an outsized percentage of what is "broken" with our educational system. But, as we listen to the finely tuned and user tested rhetoric about our broken educational system, it's worth remembering that some of the "reformers" see teachers as little more than personnel expenses. As Chris Lehmann observes, this attitude isn't something that people are going out of their way to hide:

In the spring of 2012, at the opening keynote of Education Innovation Summit, Michael Moe told a room full of education entrepreneurs that over 90% of the many billions of dollars spent on education in the United States was spent on personnel, and the only way to further monetize the education sector, as he called it, was to reduce personnel costs. To the few teachers in the room his point was clear–if you want to use technology to make money and education you have to find a way to reduce the number of teachers. And there are many powerful people who seem to agree with Mr. Moe’s statements.

The quest for personalization addresses the issue Moe raises: it allows for less money to be spent on personnel, therefore allowing companies selling personalized solutions to "monetize the education sector." Translated, this roughly equates to firing teachers in order to hand public dollars to private companies. Part of the impetus for this is buried in the innocuous phrase, "personalized learning."

In today's landscape, sitting in front of a screen using educational games is considered "personalized learning" because the user can choose their path in the game.

Spending hours on computerized adaptive tests is called "personalized learning" because the questions shift based on what you answer right or wrong.

Watching videotaped lectures is called "personalized learning" because the learner can choose to rewind or rewatch the video as many times as they want.

In the hands of a marketer, personalized learning is sold as the answer to our educational problems. With more data, they want us to believe, we can get people the content they need, just when they need it. The unspoken piece to this - and this is the subtext - is that a machine can do it better than a person. We need to be clear: that is not personalized learning. That is algorithmically mediated learning. Coming from a logical place - from a place where actual words mean actual things - it's difficult to make the argument that greater personalized learning needs to occur with fewer persons involved in the process.

I don't know if I made any lasting impact on Bob's life. For the purposes of this blog post, my N is 1, and all I have is a rambling anecdote devoid of anything that even resembles a data point. But, the notion that a person can be improved by well-timed inputs of the "right" data seems simplistic at best. One thing I do know: the day Bob learned how to break down a newspaper to study current events, he was more focused and more engaged than at any time I had seen him. When I think of truly personalized education, this is what I think about: an ongoing flow of action, reaction, conversation - and hopefully growth - that occur when people think about what they want to learn, and how they want to get there.

Image Credit: The image of the boy in the chair is reused from Rocketship’s Learning Labs & The Cost Of Personalization, by Dan Meyer, published under an Attribution license.